Neil Peart's first Modern Drummer interview

April/May 1980 issue

This interview took place after Rush had released Permanent Waves and before they were going into the studio to record Moving Pictures. Later in 1980, Neil would win as "Best Rock Drummer" in Modern Drummer's Annual Reader's Poll (this was only the second one). He would place second in "Best Recorded Performance" for Permanent Waves after Bill Bruford's "One of a Kind." After this, Neil would win "Best Recorded Performance" for every Rush album from Moving Pictures to Different Stages.

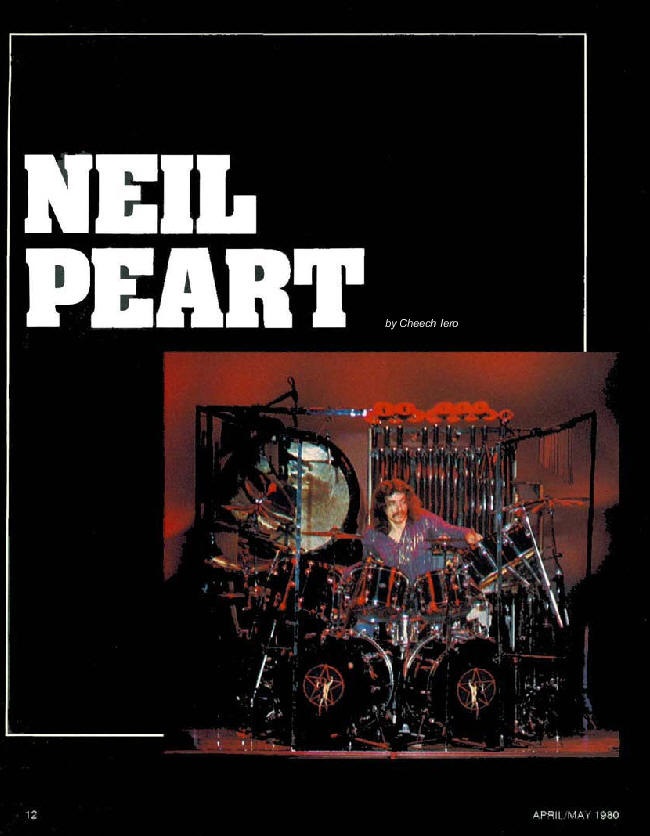

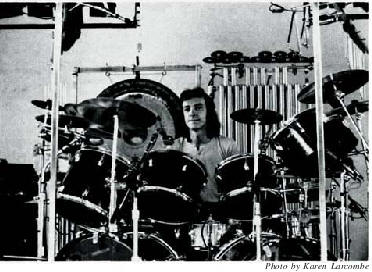

CI: Tell me a little about your set up. It's a beautiful looking set. What kind of finish does it have?

NP: It's a mahogany finish. The Percussion Center in Fort Wayne. where I get all my stuff, did the finish for me. I was trying to achieve a Rosewood. At home, I have some Chinese Rosewood furniture, and I wanted to get that deep burgundy richness. They experimented with different kinds of inks, magic marker inks of red, blue, and black, trying to get the color. It was very difficult.

CI: What is the cost of your drum set?

NP: I don't think about it. I've never figured it out. I didn't buy it all at once. I've just never thought about it.

CI: Do you enjoy the hectic schedule you keep on the road?

NP: To me, it's just the musician's natural environment. I won't say that it's always wonderful, but it's not always awful either. As with anything else, I think it's a more extreme way of life. The rewards are higher, but the negative sides are that much more negative. I think that rule of polarity follows almost every walk of life. The greater the fulfillment that you're looking for, the greater the agony you'll face.

CI: During your sound check, you not only use the opportunity to get the proper sound, but also as a chance to warm up and practice a bit.

NP: Well, sound check is a nice time to practice

and try new ideas, because there's no pressure. If you do it wrong it doesn't

matter. And I'm a bit on the adventurous side live, too. I'll try something out.

I'll take a chance. Most of the time I'm playing above my ability, so I'm taking

a risk. I think everyday is really a practice. We play so much and playing

within a framework of music every night you have enough familiarity to feel

comfortable to experiment. If the song starts to grow a bit stale I find one

nice little fill which will refresh the whole song.

NP: Well, sound check is a nice time to practice

and try new ideas, because there's no pressure. If you do it wrong it doesn't

matter. And I'm a bit on the adventurous side live, too. I'll try something out.

I'll take a chance. Most of the time I'm playing above my ability, so I'm taking

a risk. I think everyday is really a practice. We play so much and playing

within a framework of music every night you have enough familiarity to feel

comfortable to experiment. If the song starts to grow a bit stale I find one

nice little fill which will refresh the whole song.

CI: Refresh it for the rest of the group as well.

NP: Sure for all of us. We all put in a little something, a little spice. The audience would probably never notice, but it just has to be a little something that sparks it for us. And for me the whole song will lead up to that from then on and the song will never be dull.

CI: How did you become involved with Rush?

NP: The usual chain of circumstances and accidents. I came from a city that's about 60 or 70 miles from Toronto. A few musicians from my area had migrated to Toronto and were working with bands around there when they recommended me as someone of suitable style. I guess they tried a few drummers, but we just clicked on both sides. There was a strong musical empathy right away with new ideas they were working on and things I had as musical ideas. Also, outside of music we have a lot of things in common.

CI: Where has this tour taken you?

NP: Well, this isn't really much of a tour. By our terms, most of our tours last 10 months or so. This one is only 3 or 4 weeks. This is just a warm up as far as we're concerned. We've been off a couple of months. We took two weeks of holidays and then spent six weeks rehearsing and writing new material. After that kind of break, we just wanted to get ourselves out on stage. That's the only place where you really get yourself into shape. Rehearsals will keep you playing well and you'll remember all your ideas and learn your songs and stuff, but as far as the physical part of it, the feeling of being on top of your playing, you've got to have the road for that.

CI: This is a warm up for what?

NP: The studio.

CI: At what studio will you record?

NP: We will be going to Les Studio which is in Montreal. We'll record there and mix at Trident in London.

CI: When the members of Rush are composing a piece of music, is the structure determined by the feedback you receive from one another?

NP: Yes, to a large extent. It depends really on what we're coming at it with. Often times. Alex and Geddy will have a musical idea, maybe individually. They'll bring it into the studio and we'll bounce it off one another, see what we like about it, see if we find it exciting as an idea and then we get a verbal idea of what the mood of it is. What the setting would be. If I have a lyrical idea that we're trying to find music for, we discuss the type of mood we are trying to create musically. What sort of compositional skills I guess we'll bring to bear on that emotionally. The three of us try to establish the same feeling for what the song should be. Then you bring the technical skills in to try to interpret that properly, and achieve what you thought it would.

CI: Your role as a lyricist has drawn wide acclaim. How did you develop that particular talent?

NP: Well, that's really hard to put into focus. I came into it by default, just because the other two guys didn't want to write lyrics. I've always liked words. I've always liked reading so I had a go at it. I like doing it. When I'm doing it, I try to do the best I can. It's pretty secondary. I don't put that much importance on it. A lot of times you just think of a lyrical idea as a good musical vehicle. I'll think up an image, or I'll hear about a certain metaphor that's really picturesque. A good verbal image is a really good musical stimulus. If I come up with a really good picture lyrically, I can take it to the other two guys and automatically express to them a musical approach.

CI: The tune "Trees" from your Hemispheres album comes to my mind as you speak.

NP: Lyrically, that's a piece of doggerel. I certainly wouldn't be proud of the writing skill of that. What I would be proud of in that is taking a pure idea and creating an image for it. I was very proud of what I achieved in that sense. Although on the skill side of it, it's zero. I wrote "Trees" in about five minutes. It's simple rhyming and phrasing, but it illustrates a point so clearly. I wish I could do that all of the time.

CI: Did that particular song's lyrics cover a deeper social message?

NP: No, it was just a flash. I was working on an entirely different thing when I saw a cartoon picture of these trees carrying on like fools. I thought. "What if trees acted like people?" So, I saw it as a cartoon really, and wrote it that way. I think that's the image that it conjures up to a listener or a reader. A very simple statement.

CI: Do all of your lyrics follow that way of thinking, or have you expressed a more philosophical view in other songs that you have written?

NP Usually, I just want to create a nice picture, or it might have a musical justification that goes beyond the lyrics. I just try to make the lyrics a good part of the music. Many times there's something strong that I'm trying to say, I look for a nice way to say it musically. The simplicity of the technique in "Trees" doesn't really matter to me. It can be the same way in music. We can write a really simple piece of music, and it will feel great. The technical side is just not relevant. Especially from a listening point of view. When I'm listening to other people I'm not listening to how hard their music is to play, I listen to how good the music is to listen to.

CI: When you listen to another drummer, what do you listen for?

NP: I listen for what they have. There's a lot of different kinds of drumming that turn me on. It could be a really simple thing, and I don't think that my style really reflects my taste. There are a lot of drummers that I like who play nothing the way I do. There's a band called The Police and their drummer plays with simplicity, but with such gusto. It's great. He just has a new approach.

CI: Who are some of your favorite drummers?

NP:

I have a lot. Bill Bruford is one of my favorite drummers. I admire him for a

whole variety of reasons. I like the stuff he plays, and the way he plays it. I

like the music he plays within all the bands he's been in. There were a lot of

drummers that at different stages of my ability, I've looked up to. Starting way

back with Keith Moon. He was one of my favorite mentors. It's hard to decide

what drummers taught you what things. Certainly Moon gave me a new idea of the

freedom and that there was no need to be a fundamentalist. I really liked his

approach to putting crash cymbals in the middle of a roll. Then I got into a

more disciplined style later on as I gained a little more understanding on the

technical side. People like Carl Palmer, Phil Collins, Michael Giles the first

drummer from King Crimson, and of course Bill, were all influences. There's a

guy named Kevin Ellman who played with Todd Rundgren's Utopia for a while. I

don't know what happened to him. He was the first guy I heard lean into the

concert toms. Nicky Mason from Pink Floyd has a different style. Very simplistic

yet ultra tasteful. Always the right thing in the right place. I heard concert

toms from Mason first, then I heard Kevin Ellman who put all his arms into it.

You learn so many things here and there. There are a lot of drummers we work

with, Tommy Aldridge from the Pat Travers Band is a very good drummer. I should

keep a list of all the drummers that I admire.

NP:

I have a lot. Bill Bruford is one of my favorite drummers. I admire him for a

whole variety of reasons. I like the stuff he plays, and the way he plays it. I

like the music he plays within all the bands he's been in. There were a lot of

drummers that at different stages of my ability, I've looked up to. Starting way

back with Keith Moon. He was one of my favorite mentors. It's hard to decide

what drummers taught you what things. Certainly Moon gave me a new idea of the

freedom and that there was no need to be a fundamentalist. I really liked his

approach to putting crash cymbals in the middle of a roll. Then I got into a

more disciplined style later on as I gained a little more understanding on the

technical side. People like Carl Palmer, Phil Collins, Michael Giles the first

drummer from King Crimson, and of course Bill, were all influences. There's a

guy named Kevin Ellman who played with Todd Rundgren's Utopia for a while. I

don't know what happened to him. He was the first guy I heard lean into the

concert toms. Nicky Mason from Pink Floyd has a different style. Very simplistic

yet ultra tasteful. Always the right thing in the right place. I heard concert

toms from Mason first, then I heard Kevin Ellman who put all his arms into it.

You learn so many things here and there. There are a lot of drummers we work

with, Tommy Aldridge from the Pat Travers Band is a very good drummer. I should

keep a list of all the drummers that I admire.

CI: Do you follow any of the jazz drummers?

NP: I've found it easier to relate to the so called fusion actually. I like it if it has some rock in it. Weather Report's Heavy Weather I think was one of the best jazz albums in a long time. Usually, just technical virtuosity leaves me completely unmoved, though academically it's inspiring. But that band just moved me in every way. They were exciting, and proficient musicians. Their songs were really nice to listen to. They were an important band, and had a great influence on my thinking.

CI: What drew you towards drums?

NP: Just a chain of circumstances. I'd like to make up a nice story about how it all happened. I just used to bang around the house on things, and pick up chop sticks and play on my sister's play pen. For my thirteenth birthday my parents paid for drum lessons. I had had piano lessons a few years before that and wasn't really that interested. But with the drums, somehow I was interested. When it got to the point of being bored with lessons, I wasn't bored with playing. It was something I wanted to do everyday. So it was no sacrifice. No agony at all. It was pure pleasure. I'd come home everyday from school and play along with the radio.

CI: Who was your first drum teacher?

NP: I took lessons for a short period of time, about a year and a half. His name was Paul, I can't remember his last name. He turned me in a lot of good directions, and gave me a lot of encouragement. I'll never forget him telling me that out of all his students there were only two that he thought would be drummers. I was one of them. That was the first encouragement I had which was very important to me. For somebody to say to you, you can do it. And then he got into showing me what was hard to do. Although I wasn't capable of playing those things at the time, he was showing me difficult rudimental things, and flashy things. Double hand cross-overs and such. So he gave me the challenge. And even after I stopped taking lessons those things stayed in my mind, and I worked on them. And finally I learned how to do a double hand cross-over. I remember thinking how proud I would be if my teacher could see it.

CI: Did you study percussion further with other instructors?

NP: Well, it's relative. I think of myself still as a student. All the time I've been playing I've listened to other drummers, and learned an awful lot. I'm still learning. We're all just beginners. I really like that Lol Creme and Kevin Godly album. The L thing on their album stands for "learner's permit" in England. And that album is so far above what everybody else is doing, yet they're still learning. I really admire them.

CI: When you were coming up, did you set your sights on any particular goals?

NP: My goals were really very modest at the time. I would get in a band and the big dream was to play in a high school. Ultimately, every city has the place that's the "in" spot where all the hip local bands play. I used to dream about playing those places. I never thought bigger than that. For every set of goals achieved, new ones come along to replace them. After I would achieve one goal it would mean nothing. There's a hall in Toronto called Massey Hall which is a 4,000 seat hall. I used to think to play there would be the ultimate. But then you get there and worry about other things. When we finally got to play there we were about to make an album, and thought about that.

CI: Your mind was a step ahead of what you were doing at the present.

NP: Yes. I think it's human nature, not to be satisfied with what you were originally dreaming of. Whatever you were dreaming of, if you achieve it, it means nothing anymore. You've got to have something to replace it.

CI: Describe your feelings, walking on stage and looking at an audience of 35,000 screaming fans.

NP: Any real person, will not be moved by 35,000 people applauding him. If I go on in front of 35,000 people and play really well, then I feel satisfied when I come off the stage. I'm happy because those 35,000 people were excited. If we're in front of a huge crowd and I have a bad night, I still can't help being depressed. If I come off stage not having played well, I don't feel good. I don't see why I should change that. Adulation means nothing without self respect.

CI: You feel you must satisfy yourself first.

NP: I never met a serious musician who wasn't his own worst critic. I can walk off stage and people will have thought I played well, and it might have even sounded good on tape, but I still know I didn't play it the way it should be. Nothing will change that.

CI: Do you feel there are certain things that contribute to a particularly good or bad night?

NP: I don't think there is anything mystical about it at all. I just think it's a matter of polarity. I go looking for a lot of parallels. I find it in that, because certain nights it is so magical, and the whole band feels so good about how they played. The audience was so receptive and there's feedback going back and forth, and good feelings generated by the show. That has to be the ideal. That particular show might happen 5 or 6 times out of the whole 200 show tour. But that is the ideal show. Every other show has to be measured on those standards. Our average is good. We never do a bad show any more. We have a level where we're always good. Even if we're bad the show will be good. Somerset Maugham I believe said, "A mediocre person is always at his best." And that's true. If you play really great one night, you're not going to be great every night. As far as my experiences go anyway, I've never known any musician that was. I'm not. Some nights I'm good and some nights I'm not good. Some nights I think I stink. I think it's just a matter of knowing that you have an honest appraisal of what your ability should be, and know how well you've lived up to it. To me, there's no mystery about that at all. You know inside.

CI: What type sticks do you use?

NP: I use light sticks generally. I've used butt end for as long as I can remember. It gives me all the impact I need. When I'm doing anything delicate, I play matched grip with the bead end of the sticks.

CI: So you use both matched and traditional grips depending on the feeling of the music.

NP: Yes, both. I go back to the conventional grip when I have to do anything rudimentary because that's the way I learned it. It's not the best way. For anybody else learning I wouldn't advise that. I've seen a lot of drummers who could play a beautiful pressed roll with matched grip.

CI: Why do you tape the top shaft of the bass drum beater so heavily?

NP: That's an interesting trick that other drummers should know about. I break a lot of beaters off at the head, because the whole weight of my leg goes into my pedals. And I always break them where the felt part of the beater meets the shaft. They break right at the shaft, and then the shaft goes through the head. If you put that roll of tape on there you'll never break your drumhead. In fact I can still get through half a song if I have to, until the beater can be changed. The worst thing that could happen in a show would be for your bass drum to break. Anything else could be changed or fixed or re-rigged somehow. But, if you break a bass drum head the show stops. We once had to stop in the middle of filming Don Kirshner's "Rock Concert" because I broke a bass drum. So we stopped and fixed it. That's all you can do. It doesn't happen anymore, because of that idea and because Larry keeps an eye on the heads and changes them.

CI: Who mikes your drums?

NP: Our sound man lan chooses the mikes, and positions them.

CI: You have your own monitor mix during live performances, correct?

NP: Yes, Larry mixes that. That's really just my drums in a separate mix, because we have front monitors.

CI: Are the monitors on your left and right side just feeding you the drums?

NP: Yes. All I hear is myself coming from those monitor. The front monitors give me all synthesizers and vocals, and when it comes to guitar, and bass they're right beside me. There are only two other guys, I'm fortunate in that respect, so I don't need them in my monitors. I have direct instruments to my ears which to me is the best. I'd rather have that than to fool around with the monitors. And the stuff the other guys need in their monitors I get indirectly, because it's pointing at them, so I also hear it. I know a lot of drummers who prefer to have the whole mix in their monitors, and in some cases need the whole mix in their monitors.

CI: Have you ever worn earphones while playing live?

NP: No, not really, they fall off. I even had a lot of trouble in the studio keeping them on. I went through all kinds of weird arrangements, getting the cord out of my way. It's just not worth it, I like to hear the natural sound.

CI: What are your thoughts on tuning?

NP: Concert toms are pretty well selfexplanatory. I just know the note I want to achieve and tighten them up.

CI: Do you use a pitch pipe, get the note from the keyboard or just hum the note you're after?

NP: I've been using the same size drums for several years, and I just know what note that drum should produce. When you combine a certain type of head with a certain size drum I believe there is an optimum note, which will give you the most projection and the greatest amount of sustain. With the concert toms I just go for the note. I have a mental scale in my head. I know what those notes should be. By now it's instinctive. With the closed toms, I start with the bottom heads. I'll tune the bottom heads to the note that drum should produce, and then tune the top head to the bottom.

CI: How often do you change the heads on your drums?

NP: Concert tom heads sound good when they're brand new, so they get changed a bit differently. They last through a month of serious road work. The Evans Mirror Heads are used on the tom toms and take a while to warm up. It takes a week to break them in. I don't change those much more than every six weeks or so. They do start to lose their sound after a while. You start to feel they're just not putting out the note they should be. Then you say, "I hate to do it but let's change the heads." I like Black Dots when they're brand new. I used to use those on my snare, and the Clear Dots also sound good when they're brand new. But the Evans heads don't. It takes awhile. I've gone through agonies with snare drums. I guess most drummers do. I had an awful time, because there was a snare sound in my mind that I wanted to achieve. I went through all kinds of metal snares. And I still wasn't satisfied. It wasn't the sound I was after. Then my drum roadie phoned me about this wooden Slingerland snare. It was second hand. Sixty dollars. I tried it out and it was the one. Every other snare I've tried chokes somewhere. Either very quietly, or if you hit it too hard it chokes. This one never chokes. You can play it very delicately, or you can pound it to death. It always produces a very clean, very crisp sound. It has a lot of power, which I didn't expect from a wooden snare drum. It's a really strong drum. I tried other types of wooden snare drums. I tried the top of the line Slingerland snare drum. This one was a Slingerland but very inexpensive. I've tried other wooden snares, but this was the one, there's no other snare drum that will replace it for me.

CI: What has been done to the inside of your drum shells?

NP:

All of the drums with the exception of the snare have a thin layer of

fiberglass. It doesn't destroy the wood sound. It just seems to even out the

overtones a bit, so you don't get crazy rings coming out of certain areas of the

drums. You don't get too much sound absorption from the wood. Each drum produces

the pure note it was made to produce as far as I'm concerned. There's no

interference with that either in the open toms or the closed toms. The note is

very pure and easy to achieve. I can tune the drums and when I get them to the

right note I know the sound will be proper.

NP:

All of the drums with the exception of the snare have a thin layer of

fiberglass. It doesn't destroy the wood sound. It just seems to even out the

overtones a bit, so you don't get crazy rings coming out of certain areas of the

drums. You don't get too much sound absorption from the wood. Each drum produces

the pure note it was made to produce as far as I'm concerned. There's no

interference with that either in the open toms or the closed toms. The note is

very pure and easy to achieve. I can tune the drums and when I get them to the

right note I know the sound will be proper.

CI: Why do you use the same size double bass drums instead of two different size drums to achieve two different bass voices?

NP: I don't know. I can't see the point of it really. I'm not looking for different sounds. I don't use bass drums for beats or anything like that. My double bass drums are basically for use with fills. I don't like them to be used in rhythms. I like them to spice up a fill or create a certain accent. Many drummers say anything you can do with two feet, can be achieved with one. That just isn't true. I can anticipate a beat with both bass drums. That is something I learned from Tommy Aldridge of the Pat Travers Band. He has a really neat style with the bass drums. Instead of doing triplets with his tom toms first and then the bass drums, which is the conventional way, he learned how to do it the other way, so that the bass drums are anticipated.

CI: Giving it a flam affect?

NP: In a sense. It has an up sort of feel. You could just be playing along in an ordinary 4 beats to the bar ride and all of a sudden stick that in. It just sets that apart. When you listen to it on the track, it sounds strange. It really works well and it's handy in the fills. You can be in the middle of a triplet fill and all of a sudden you can leave your feet out for a beat and bring them back in on the beat. It's really exciting. And I like to interpose two bass drums against the hi-hat too. There are a few different things I do where I throw in a quick triplet or a quadruplet using the bass pedals and then get right over to the hi-hat. I'll complete my triplet and by the time my hand gets over to the hat my foot is already there. So you'll hear almost consecutive left bass drum and hi-hat notes. If you want a really powerful roll, there's nothing more powerful than triplets with two bass drums. I could certainly get along without two bass drums for 99% of my playing. But I would miss them for some important little things.

CI: Did you go to the Zildjian factory to select your cymbals?

NP: No, I must admit I've cracked so many cymbals, that would be futile. I just know the weights that I want to get and if I have one that's terribly bad, I'll take it back. I go through an awful lot of crash cymbals. I hit them hard and they crack. Especially my 16" crash which is my mainstay, and my 18" crash.

CI: Where do you buy your cymbals?

NP: From the Percussion Center. I actually haven't seen their store in many years. Most of our business is done by them shipping the merchandise out to us, or Neil Graham comes out from the store. He brought me my new drums a couple of weeks ago. I know he has a lot of imagination; if I want something crazy, he'll come up with it. If I want crotales on top of the tubular bells, or a temple block mounted on top of my percussion, he can do it. When you present him with an idea, he thinks of a way to achieve it. He never let me down in that respect. He built my gong stand. The gong stand mounts on the tympani and is attached to the mallet stand.

CI: With the extensive set-up that you use, I'm wondering why you do not use electronic percussive devices.

NP: It's a matter of temperament really. I don't feel comfortable with wires and electronic things. It's not a thing for which I have a natural empathy. It's not that I don't think that they're interesting or that there aren't a lot of possibilities. But personally, I'm satisfied with traditional percussion. I have distrust for electronic and mechanical things. I've got enough to keep me busy, really. When I look at my drums, the five piece set up is the basis of what I have. I might have hundreds of toys, but for me most of my patterns and most of my thinking revolves around snare drum, bass drum, hi-hat, and a couple of tom toms. But there's more to it than that. I can add a lot more. I don't understand the people who are purists or fundamentalists, who would look at my drum kit and say, 'All you need is four drums.' That makes me as mad as looking down on someone who has only four drums. I'm not afraid to play on only four drums, but there's more that I can contribute to this band as a percussionist. I'm certainly not a keyboard percussion virtuoso by any means, nor do I expect to be. I just want to be a good drummer at this point in my life. Having eight tom toms to me is excellent, because I can do that many more variations of sounds. So you're not hearing the same fill all the time, or the same sort of patterns. There are different notes, different perspectives of percussion. To me it sounds like a natural evolution. I couldn't understand anyone who would look at it with bitterness, or reproach, because I don't neglect my drumming because of that. When I'm not busy drumming, I have something else to do. And the guys show me the notes to play and I play them. I know Carl Palmer spends a lot of time on keyboard percussion and I admire him for that. He's getting quite proficient. Bill Bruford's getting amazing on keyboard percussion, because he's devoted the time and the energy that it takes to become a proper keyboard percussionist. I admire that to no end. I spend a lot of time thinking about composition, and drumming has to be the prime musical force. I spend a lot of time working with words. I look at that as a simultaneous education while I'm refining my drumming skills.

CI: Do you use lyrics as a guide to your drumming?

NP: Not after the fact. Once we have agreed on the musical structure and arrangement, it then becomes a purely musical thing. Obviously, if there's a problem in phrasing I might have to rewrite the structure. But for the most part I forget about the lyrics and listen to the vocals. Getty's interpretation is really when it becomes an instrument, so there's a way I can punctuate the vocals or frame the vocals somehow musically.

CI: What are some of your thoughts on drum soloing?

NP: I guess there are mixed feelings. How musical it is depends on the drummer. I find it very satisfying. I guess a lot of drummers do improvise all the way through their solo. I have a framework that I deal with every night, so I have some sort of standard where it will be consistent. And if I don't feel especially creative or strong, I can just play my framework and know it will be good. But certain areas of my solo are left open for improvisation. If I feel especially hot, or if I have an idea which comes to me spontaneously, I have plenty of room to experiment. I try to structure the solo like a song, or piece of music. I'll work from the introduction, and go through various movements, and bring in some comic relief. Then build up to a crescendo and end naturally. I can't be objective. Subjectively, I enjoy doing it and like listening to it. It's a good solo. Nondrummers have told me it's a nice drum solo to listen to.

CI: Do you have any advice for the young drummers with aspirations of someday playing in a musical situation similar to your own?

NP: I used to try to give people advice but the more I learned, the more I realized that my advice could only be based on both my values and my experiences. Neither of which are going to be shared by very many people. I would say to them, 'Go for what you're after.' I can't get much more complicated that that. I don't feel comfortable telling people what to do.

CI: Have you ever taught private students'?

NP: No, I haven't. I've been asked to do clinics which I'm interested in, but fearful of. But I would like to get into doing that, relating to people on that level. I like to talk about drums. I like to talk about things I'm interested in. For me to talk about things I'm honestly interested in, and obviously drums is one of them, is foremost.

CI: What are your thoughts on interviews?

NP: I won't do an interview for a promotional reason. I do them because I like to get my ideas out. Sometimes, I can talk about something in an interview and realize that I was totally wrong. And I'll have had the opportunity to air those thoughts out which most people don't. You don't have conversations with your friends about metaphysics, the fundamentals of music, and the fundamentals of yourself really. When I do an interview, I look for an ideal. I'm looking for an interview that's going to be stimulating, and I'll get right into it. Just sit for hours and relate. That's an ideal, like an ideal show. It doesn't happen that often.

CI: Before setting up your kit, your roadie Larry Allen cleaned and polished each cymbal to a high gloss and cleaned all the chrome. Does he take this great care as per your instruction, or is this something Larry does on his own? '

NP: That's a reflection of Larry's care. He takes a lot of pride in having the set sparkle and the cymbals shining. On his side I relate to that, but it doesn't affect me really one way or the other.

CI: Do you hear a difference in the brilliance of the sound when your cymbals are clean instead of tarnished?

NP: No, not really. It's hard to justify really. To me a good cymbal sounds good, and a bad cymbal doesn't sound good. That's the way I feel about it. My 20" crash has a very warm, rich sound with a lot of good decay. I don't think dirt would improve that.

CI: Some drummers feel that as the cymbal is played, gets dirty, and gets tarnished, it takes on a certain character all its own. Do you think it is really the aging process which is the factor?

NP: Yes, I think age has something to do with that. But the cymbal is metal, how can dirt make it sound better? If you don't want the decay, stick a piece of tape on it. It'll do the same thing dirt will do. It may be true that dirt is a factor. But it won't give it a warmer sound by definition, because the note of the cymbal is still the note of the cymbal.

CI: The dirt will only affect the sustain.

NP: Exactly. So if you want a shorter sustain, get it dirty. My cymbals are chosen for the length of decay that I want. And a certain frequency range. The amount of decay is especially crucial.

CI: Tell me about that Chinese cymbal you're using. It sounds great!

NP: I had an awful time trying to get into China cymbals. I bought an 18" pang, just looking for the Chinese sound. It had a good sound and I found myself using it for different effects. But it's almost a whispery, electronic sound. When I listen to its sound in the studio, or on a tape it sounds like a phaser. It has a warm sort of sound, but it didn't have the attack I was looking for. So I got the Zildjian China type which had that, but also a lot of sustain. Larry picked this one up at Frank's Drum Shop. It was made in China. It's a 20" with a little more bottom end to its sound.

CI: For the size of your set up I was somewhat surprised to see you using 13" hi-hats. Why 13V?

NP: I've always used 13's. I use a certain hi-hat punctuation that doesn't work with any other size. I've tried 14's, and everytime we go into the studio our coproducer Terry Brown, wants me to use 14" hi-hat cymbals. I've tried them. I'm an open-minded guy. But it just doesn't happen for me.

CI: Are they just conventional hats?

NP: Just conventional, regular old hihats. We work with a band a lot called Max Webster, and their drummer and I work very closely, listening to each other's drums. Webster told me not to change that hi-hat, because for any open hat work or any choke work, it's so quick and clean. It just wouldn't work with 14's. The decay is too slow.

CI: Are you talking about that particular pair of 13's or any 13's?

NP: Well any 13's for me. I've gone through about three sets of I3's in the last 8 or 9 years. And they've all sounded good. When I found myself to be one of the only drummers around using 13's, I tried others, but either my style developed with 13" cymbals or the 13" cymbals were an important part of my style.

CI: You are using Evans heads on your toms.

NP: Yes. The Evans heads have a nice attack which gives a good bite from the drums. At the same time you never lose the note. I play with a lot of open drums, open concert toms. But my front toms and my floor toms are all closed with heads on the bottom. I never lose the note on account of that. With certain types of acoustical surroundings, open drums just lose everything, all you hear is a smack. I get that with my concert toms. I hear that with other drummers. If you're in a particularly flat hall, or if the stage area is particularly dead, it kills the note of the drums. I think it's easier to get a good sound with open drums. I've been talking to people about this lately, and developing a theory. I think that perhaps, especially with miking, it's easier to get a good sound with open drums. But I think that a better sound can be achieved with closed drums. A more consistent sound. I think that over a range of hundreds of different acoustical surroundings, closed drums have a better chance of sounding good more often. That's just a theory. It depends on a number of things of course. I open up my bass drums in the studio, but I leave the toms closed.

CI: Yet for your live performance, I see you have left both heads on the bass drums. Why?

NP: I think I get a rounder note, and a more consistent bass drum sound. And our sound man's happy with both heads on. We just have a small hole in the front head and a microphone right inside.

CI: I noticed you use a microphone under your snare drum.

NP: Yes, I use an under snare mike for the monitors only. Which Ian doesn't use out front. I don't use the over snare mike in the monitors, because I'm getting all of the middle I need out of the drum itself. It's the high end that gets lost in the ambient sound of the rest of the band. The high end gets lost first.

CI: What about in the studio?

NP: In the studio sometimes both, but usually the top.

CI: In the studio, do you use one mike to catch the snare and the hi-hat or is that done separately?

NP: Just one mike on the snare alone, and the hi-hat has a separate mike. It's a logistical thing. We have to go for close miking. Just about everything is individually miked. There are three overheads to cover the cymbals, one separate over head for the China-type. I have a certain set of long, tubular wind chimes that have to be heard at a particular point so they have a mike. There's a mike for the tympani, there's two mikes for the orchestra chimes and they also pick up the crotales. There's also a separate mike for the glockenspiel. If I want to try to inject that much subtlety into our music, the glockenspiel has to be miked closely or it won't exist. It's crucial. Miking is a science that I can't talk about with much conviction. I don't know a lot about it other than a few bits of theory I picked up in the studio. As far as live miking goes, I'm pretty ignorant I must admit. I'm just trying to get my drums to sound good to me, and then it's up to the sound man to make them sound good in the house.

CI: Could you tell me a little about your recent album?

NP: There's quite a variety of things this time. We didn't have any big ideas to work on so it's a collection of small ideas. Individual musical statements. We got into some interesting things, and some interesting constructions too. We built a whole song around a picture. We wanted to build a song around the phenomena called Jacob's ladder, where the rays break through the clouds. I came up with a couple of short pieces of lyrics to set the musical parts up. And we built it all musically trying to describe it cinematically. As if our music were a film. We have a luminous sky happening and the whole stormy, gloomy atmosphere, and all of a sudden these shafts of brilliance come bursting through and we try to create that musically. There's another song called "The Spirit Of Radio." It's not about a radio station or anything, it's really about the spirit of music when it comes down to the basic theme of it. It's about musical integrity. We wanted to get across the idea of a radio station playing a wide variety of music. For instance the "Spirit Of Radio" comes from the radio station at home called CFMY and that's their slogan. They play all great music from reggae to R&B, to jazz to New Wave, everything that's good or interesting. It's a very satisfying radio station to me. They have introduced me to a lot of new music. There are bits of reggae in the song and one of the verses has a New Wave feel to it. We tried to get across all the different forms of music. There are no divisions there. The choruses are very electronic. It's just a digital sequencer with a glockenspiel and a counter guitar riff. The verse is a standard straight ahead Rush verse. One is a new wave, a couple reggae verses, and some standard heavy riffing, and as much as we could possibly get in there without getting redundant. Another song that we also did in there, "Free Will" is a new thing for us in terms of time signatures. I mentioned before that we experiment a lot with time signatures. I get a lot of satisfaction out of working different rhythms and learning to feel comfortable.

CI: What time signatures are you using during this tune?

NP: We work in nearly everyone that I know of that's legitimate. All of the 5's, 7's, 9's, ll's, 13's, and combinations thereof. There were things on the last album that were 21 beat bars by the time they were actually completed. Because they had a 7 and a 6; a 5 and a 4; or 7. 6, 7, 6, 7, 6, 5. I get a tremendous amount of satisfaction making them feel good. I don't think that you have to play in 4/4 to feel comfortable.

CI: How did you develop your understanding of those odd meters?

NP: I remember figuring out some of Genesis' things. That was my first understanding of how time signatures were created. And I'd hear people talking about 7, and 5 and if they played it for me I could usually play along. But I didn't understand. I finally got to understand the principle of the common denominator. Once I understood it numerically I found it really easy to pick up the rhythm. Then you take on something just as a challenge, and turn it into a guitar solo in 1 3/8, and find a way to play that comfortably and make changes. As I would change dynamically through a 4/4 section. There would be certain ways that I would move it, try to apply those same elements to a complicated concept. I think Patrick Moraz put it best. He said, "All the technique you have in the world is still only a method of translating your emotions." So we're coming back with that acquired technique. There's a lot of truth in Moraz's statement because now we're finding out as we have gone through all those, some of them honestly were technical exercises. You have to say that sometimes you get excited about playing something just because it is a difficult thing. And certain times we would get into the technical side of it, but become bored with it. Now we're finding out how to bring those technical ideas back and put them into an exciting framework. We have a song that's almost all in 7 and has some alternating bars of 8 and the chorus that goes into it again is in 4. It's all very natural to play. I can play through the whole song and I don't count once. The only thing I count are pauses. If I'm stopping for 8 beats or something I'll count that off with my foot. But when I'm playing I just don't count, unless I have to, for meter reasons. This is probably a common experience, but slower things for me are the most difficult to keep in meter. If I'm playing really slow straight 4's, I count that, but if I'm playing really fast in 13, I don't dare count, I just play it. We were talking earlier about music taking patterns as a musician. I think it does that. I have a program in my head that represents the rhythmic pattern for a 13, or a 7, or a 5. And I can bring those out almost on command, having spent a lot of time getting familiar with them. It's so exciting when you start to get it right the first few times and you're putting everything you have into it. That's the ultimate joy of creating. That joy is such a short lived thing, most of the time you don't have time to enjoy it. Most times when I write a song the moment of satisfaction is literally a matter of a few seconds. All of a sudden you see it's going to work and you're going to be happy with it, and then bang you're back into working it again. You're thinking how am I going to do this? Whether it's lyrically or musically, the moment of satisfaction is very fleeting.