|

|

| Home | Next |

Updated: 12/06/2017

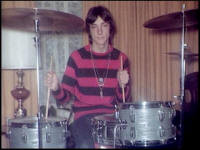

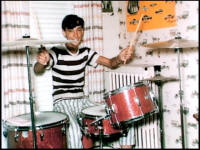

Neil's first drum kit: Stewarts

It was a three piece, red sparkle Stewart outfit (I still remember it cost $150), bass drum, snare drum, and tom-tom, with one small cymbal. It was one of those unbearably exciting days in life, waiting for them to arrive, then setting them up in the front room and playing and playing the only two songs I knew, "Land of a Thousand Dances"... and "Wipeout." (from Traveling Music, page 69)

The Drums? Well, they're Stewarts, of course, with an 18" Capri bass drum I got in a trade from my friend, and featuring the finest Ajax cymbals from Japan. (As my colleague Lerxst pointed out, those were the days when "Made In Japan" really meant something―none of your quality materials and meticulous workmanship then, boy.)" (From the Test for Echo tour book).

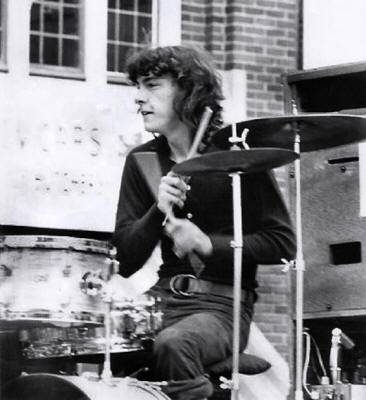

Neil's second drum kit: Rogers

A set of Rogers drums, in a gray ripple finish They were so beautiful, but they cost a fortune: $750." (from Traveling Music, page 71).From Neil Peart's May, 2010, update "Time Machines":

It was a summer Saturday in 1970, and I was playing with the band J. R. Flood in St. Catharines, Ontario. We were set up on the back of a flatbed trailer on James Street, closed to traffic for a Saturday "whoopee." The idea was for us to entertain the youngsters, confound the adults, and share a $250 fee. Pictured are the late organist Bob Morrison and guitarist Paul Dickinson, and we had bass guitarist Wally Tomczuk and singer Gary Luciani. I was seventeen.

.

Looking at this particular image can send me off in so many directions. My eyes go straight to those drums, the first good set I ever owned: gray ripple Rogers. Not long after that photo was taken, I stripped them down to the bare shells in my bedroom, painstakingly disassembling all of the hardware, and covered the gray ripple wrap with "chrome" wallpaper, to emulate Keith Moon's Tommy kit. Only two years or so previously, I had added the second eighteen-inch bass drum (little cannons like that represented a certain "style" then—a hangover from mod, I guess), and another twelve-inch tom. In addition, I had a fourteen-inch floor tom, a chrome "Powertone" snare (a model below the Dynasonic I coveted), thirteen-inch high-hats on a stand with a homemade height-extender, and two Zildjian cymbals, a twenty-inch and an eighteen.

That day, I remember my twenty-incher was cracked, and I couldn't afford a new one. A friend of the band's, Greg, was a local drummer who had a somewhat less violent playing style than my own, but he lent me his twenty-inch Zildjian for that show. I still consider that a brave and generous act. (I didn't break it.)

My pantlegs are rolled up like a clown to prevent the bass-drum-pedal beaters from fouling in my flares (I use a bicycle clip these days), and the drumsticks are played backwards, "butt-end," because I couldn't afford to replace broken ones, so turned them around and used the other end. I'm sitting on a little square pillow ("liberated" from my mom) atop an upturned metal barrel (in which my dad's farm equipment dealership sold calcium carbide for bird-scarers—sigh, so much needs to be explained when you're telling about a time machine: those bird-scaring devices looked like a long megaphone atop a box, and they made a loud explosive noise from time to time, to scare birds out of orchards and vineyards). That steel barrel also served as a hardware case, because after the gig I could fill it with the stands and hardware.

A drumset is a time machine, literally speaking—a machine for keeping time—though a drummer has to be the clockwork device to subdivide rhythm—to bring the time.

In those days, I was not that drummer.

In the opening photo, guitarist Paul is giving me what I can only describe as an "incredulous" look (he was both disciplined and disciplinarian, and I learned a lot from Paul in those days, like how to watch his tapping foot—a time machine if ever there was one—to keep the tempo). At that moment, I was probably racing away. When I hear the demos we made in those days, I find myself thinking, "For heaven's sake—give that drummer a valium!" (Or a metronome.)

The spectacles on the optician's sign remind me of the eyes on the billboard in The Great Gatsby, which Fitzgerald used as a symbol for an impassive onlooker, a remote, uncaring deity, seeing all, changing nothing. "The stars look down."

To any drummer who has sweated over a particular set of drums, they represent another kind of time machine—like a classic violin or guitar, a part of one's life. Still, I don't get emotional about my old drumsets, and have given most of them away.

Happily, the Rogers are still in the possession of my friend Brad, who has restored them beautifully, stripping off the cheesy chrome wallpaper to reveal the classic gray ripple finish. A couple of years back I had the opportunity to play them again, in Brad's basement, with him playing guitar, and we had a fine time.

No, I didn't feel transported into the past, but it was fun to share a piece of it. And I wished I could have communicated a few observations to that kid who used to play those drums, so many long years ago. Even just to tell him, "Your 'time' will come."

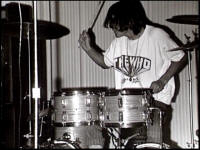

Neil's Rogers drum kit with chrome wrap (playing with J.R. Flood, 1970)

"... I stripped them down to the bare shells in my bedroom, painstakingly disassembling all of the hardware, and covered the gray ripple wrap with 'chrome' wallpaper, to emulate Keith Moon's Tommy kit."

Neil's Rogers kit today

The Rogers kit is owned by Neil's friend, Brad, who has restored it to the gray ripple finish:

Happily, the Rogers are still in the possession of my friend Brad, who has restored them beautifully, stripping off the cheesy chrome wallpaper to reveal the classic gray ripple finish. A couple of years back I had the opportunity to play them again, in Brad's basement, with him playing guitar, and we had a fine time.