7. 1990s influences |

|

The 1990s provided two essential influences for Peart: First, after years of drum machines providing the backbeat for modern music, the pendulum swung back toward real drummers. Grunge exploded onto the popular scene with Nirvana's "Smells Like Teen Spirit." As Peart explained to Modern Drummer:

We got to the '90s and suddenly all sorts of bands came up with drummers who are playing. The recent bands coming out of Seattle and from across the States are revealing some fantastic drummers. Somehow, the torch was passed. These drummers were practicing and improving throughout the '80s, preparing for the time when they'd get the chance. I honestly feel this is a very exciting time for drumming. It's so gratifying to hear it come back, and come back with such a vengeance." (Modern Drummer, December 1994)

Second, Peart rediscovered his big band jazz roots through his participation in the Burning for Buddy Memorial Concert in 1991. This led to further exploration of the swing style and especially how it could help him break out of the metronomic stiffness that had crept into his playing (the result of playing along to perfect metronomic time with click tracks and sequencers). So began Peart's 20-plus year odyssey to rediscover "chops and groove," first through Buddy Rich's work, and later with teachers, Freddie Gruber and Peter Erskine.

Buddy Rich (1991) via Burning for Buddy projects

In 1991 Peart rediscovered Buddy Rich and big band jazz when he played at the Buddy Rich Memorial Concert in New York City. This performance would set in motion a series of events that would change the course of Peart's approach to the drums. In his reply to Cathy Rich, who was producing the concert, he wrote:

As a rule, I do my work with Rush, and hide behind a low profile otherwise... But even my own rules are made to be broken, and this seems like a worthwhile occasion to come out of my self-imposed shell. Not only is it an opportunity to “give something back,” but also an opportunity to fulfill a long-time ambition of my own—to play behind a big band. (Traveling Music: The Soundtrack to My Life and Times, p. 29).

However, the performance didn't go as well as Peart had hoped.

Unfortunately, it turned out to be a difficult and disappointing experience for me. With minimal rehearsal time, there had been no opportunity to discover that the rest of the band was playing a different arrangement of “Mexicali Nose” than the one I had learned, and during the performance I was unable to hear the brass section at all. I struggled through it, and managed to hold it together, but after, I felt very let down by the experience I had so anticipated, and down on myself about it. (Traveling Music: The Soundtrack to My Life and Times, p. 30)

On the drive back from New York to Toronto, Peart came up with the idea to produce a Buddy Rich tribute album, so that the would have a chance to play big-band music again, albeit in a more controlled studio setting. The result was two commercially and critically successful Burning for Buddy albums that Peart produced with the Buddy Rich Band and Rich's daughter Cathy Rich, featuring some of the world's most celebrated drummers including: Simon Phillips, Dave Weckl, Steve Gadd, Steve Smith, Matt Sorum, Manu Katche, Billy Cobham, Rod Morgenstein, Max Roach, Kenny Aronoff, Omar Hakim, Joe Morello, Bill Bruford, Marvin "Smitty" Smith, Steve Ferrone, and Ed Shaughnessy.

Read Peart's comments about all the drummers he worked with.

During the recording process of Burning for Buddy, Peart observed a noticeable improvement in drummer Steve Smith's playing and technique. When he asked his secret, Smith told him about how he'd studying with Freddie Gruber. Not long after that Peart arranged to spend a week with Gruber.

At the time, many wondered why a drummer of Peart's abilities and accomplishments would need to take drum lessons? The answer was that Peart was always searching for ways to improve his approach to his instrument. This search for excellence was the reason he'd become the drummer he was and why so many people admired him.

What fans might not have known was that Peart had reached a plateau in his playing and abilities. While he could certainly do the job with Rush, the years of chasing perfect time had taken a toll on his feel. Freddie Gruber would be the teacher to help him break out of his current approach. This study would take him one-and-a-half years, putting on hold a new Rush album and tour.

As if to document the time and effort it had taken, Peart produced his first instructional video, A Work in Progress, where he detailed Gruber's influence on his drumming on the Test for Echo album. Watching Peart perform on this video is like seeing a different drummer. There's a brand-new drum layout, with toms and cymbals moved to new positions. The snare drum is now at navel level, and for the first time he used a traditional grip with the tips of the stick (not the butt ends). But, as Peart explained, even after making all those changes, Peter Collins (producer of Test for Echo) said to Peart, "Well it still sounds like you." At first the comment was upsetting, but then Peart came to another realization.

Eventually I realized that was the highest of compliments. If I can change everything about the way I play, from the way I hit things, to my hopefully improved time sense, to the drums themselves, even to the drumheads—I went with white Ambassadors for the first time just for the most complete change possible—and our co-producer doesn't notice a difference, I must have a style of my own. Whatever passes for my "style" is strong enough to transcend all of those changes. (Modern Drummer, November 1996)

This quest for "chops and groove" would continue into the next century.

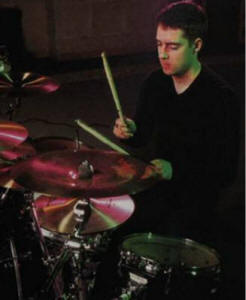

Chad Gracey - Live

Just a few of the newer guys I've been enjoying include Dave Abbruzzese of Pearl Jam, Matt Cameron from Soundgarden and Temple Of The Dog—I love his playing. And Chad Gracey from the band Live, who plays just what you want to hear. (Modern Drummer, February 1994)

Max Roach

On the other hand, you’ve got to be careful about surrendering too easily to your assumed limitations. I have talked before about that determination in regard to playing in odd times, and a good example was the 3/4 exercise, like [Max Roach’s famous solo] “The Drum Also Waltzes.” When I first tried that, laying down the bass drum and hi-hat ostinato, I couldn’t seem to play anything over it. I thought to myself, “I can’t do this.” But I persevered, day after day, and pretty soon, I was surprising myself. And from then on, until today, it remains one of my favorite musical vehicles. (Modern Drummer, February 1994)

Pat Torpey - Mr. Big

Pat's an accomplished drummer with a background in some areas of drumming that I'm not familiar with-Latin, for instance. He showed me some great patterns to practice. And I was just exploring any possibility I could come up with. I'd play an ostinato pattern and then try to get my other limbs to work over the top of it. It was an ideal activity for me to be doing before a show. It kept my drumming alive for me during the last part of the tour, when normally I'm feeling like I've been out for too long. (Modern Drummer, February 1994)

-------------

Asked in 1992 by Powerkick magazine about drummers who were impressing him, Peart answered with the names of the following drummers:

Mike Bordin - Faith No More (1992)

I like Mike Bordin of Faith No More. He is a tremendously schooled player...he pays homage to the past and has applied it to playing well.

Matt Cameron - Soundgarden (1992)

I really like the guy from Soundgarden [Matt Cameron]. I like his playing a lot...he has a lot of room to shine and I enjoy his playing immensely.

Dave Abbrezezze - Pearl Jam (1992)

He has a great sense of the groove, but also excels at embellishment. I think it's been very nice in the early nineties to see a resurgence of real drums

Bands that opened for Rush in the 1990s:

Presto

Mr. Big (Pat Torpey), Chalk Circle (Karl David Fielding), Voivod (Michel Langevin)

Roll the Bones

Eric Johnson (possibly Tommy Taylor), Vinnie Moore (unknown), Primus (Tim Alexander), Mr. Big (Pat Torpey), Andy Curran (unknown)

Counterparts

Candlebox (Scott Mercado), The Melvins (Dale Crover), Primus (Tim Alexander), The Doughboys (Brock Pytel), I Mother Earth (Christian Tanna)

No opening bands after Counteparts tour