2. Early influences: R&B and rock roots: 1960s-1970s |

|

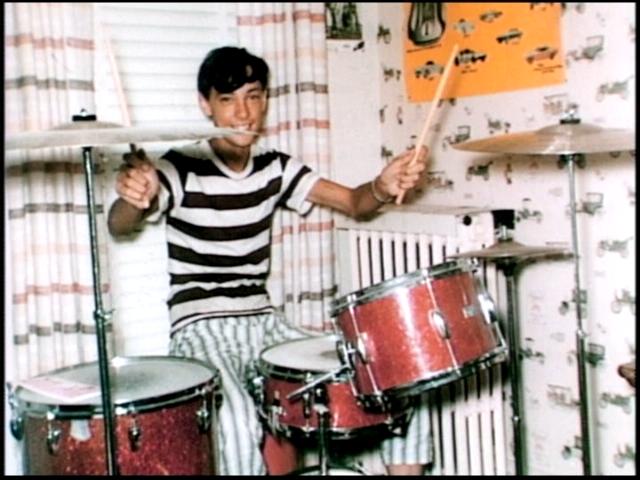

After Glen Peart introducing his son to big band jazz, the next most important development for Neil was getting a transistor radio. It would be the spark that ignited a more serious interest in music and, eventually, rock music. As he wrote in his article, "A Port Boy's Story" for the St. Catharines Standard:

In early adolescence, my hormones attached

themselves to music. Mom and Dad gave me a transistor radio, and I

used to lay in bed at night with it turned down low and pressed to

my ear, tuned to pop stations in Toronto, Hamilton, Welland, or

Buffalo. I still remember the first song that galvanized me:

"Chains," a simple pop tune by one of those girl groups (The

Cookies), with close harmonies syncopated over a driving

shuffle. No great classic or anything, but as I listened to that

song on my transistor, suddenly I understood. This changed

everything.

Rhythm especially seemed to affect me,

in a physical way, and soon I was tapping all the time — on tables,

knees, and with a pair of chopsticks on baby sister Nancy's playpen.

At first Mom and Dad probably thought I had some kind of nervous

affliction, but they decided to try occupational therapy — for my

thirteenth birthday, they got me drum lessons. This changed

everything even more. (St.

Catharines Standard, 24 June 1994)

R&B and Soul

In 1963, Peart heard rhythm & blues music played in his uncle's band. Like jazz, R&B would provide another musical template to return to throughout his career.

...It might be said that for those of us raised on the painfully white pop music of the late ’50s and early ’60s, R&B music was the underground music, the alternative music of the times. I didn’t think of it as listening to "black music"; I just knew I liked the rhythms, the intense, passionate vocals, and the way my pulse rate increased when I heard that horn line in "Hold On, I’m Coming," even played by a teenage white boy on a Fender Telecaster in my uncle’s band. (Traveling Music, p. 67)

In late 1965, before Peart picked up a pair of drum sticks, he watched the T.A.M.I. (Teenage Music International) Show movie. He was particularly impressed by James Brown, who "gave an intense, theatrical demonstration of what soul music was all about." (Traveling Music, p. 136).

In 1994, Peart talked to Modern Drummer about how the R&B influence returned more prominently on Counterparts:

I think the nature of the songs on this album brought out a lot of my R&B background, and I don't think that's an area I'm known for. But all the first bands I played in were blue-eyed soul bands. I played a lot of James Brown and Wilson Pickett tunes, because in the Toronto area that's what was popular at the time. All of us grew up playing "In The Midnight Hour." R&B is a part of my roots, and as a band I think we all played it and enjoyed it. But as we developed we drifted off into the other styles of the 60's, and when the British progressive bands came along we went in that direction. (Modern Drummer, 1994)

Early rock drumming influences (1960s)

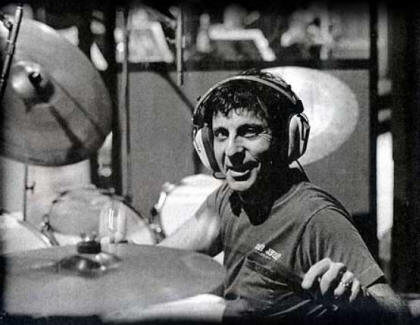

Peart's first teacher was Don George, with whom he studied at the Peninsula Conservatory of Music in St. Catharines. Peart said of George, "Don gave me a strong enough direction toward what I needed to know that I could follow it through those decades. ("Witness to the Fall", NeilPeart.net, November 2012)

After proving his interest to his parents by taking lessons and practicing for a year, Peart finally received his first drum kit.

It was a three piece, red sparkle Stewart outfit (I still remember it cost $150), bass drum, snare drum, and tom-tom, with one small cymbal. It was one of those unbearably exciting days in life, waiting for them to arrive, then setting them up in the front room and playing and playing the only two songs I knew, "Land of a Thousand Dances"... and "Wipeout." (Traveling Music, p. 69)

Ron Wilson: The Surfaris and drummer on "Wipeout"

In an interview with drummer Michael Shrieve in 2012, Peart talked about the importance of "Wipe Out" and why he sometimes plays it on his birthday, usually in his drum solo:

When I got my first little 3-piece drum set of drums, that’s the first thing I played on it. So that one always comes out (on my birthday).

Hal Blaine: 35,000 recordings

When I was growing up, I played along to the radio, so I played along to Simon & Garfunkel, The Beach Boys, The Association, and The Byrds, and I was really playing along to Hal Blaine. He played on all of those records and so many more. There was another drummer who said that he was shattered to find out that his six favorite drummers were all Hal Blaine! ("Neil Peart's Six Favorite Drummers are Hal Blaine," Gibson.com, 2011)

Blaine, whom Peart watched in the T.A.M.I. Show movie in 1965, would have a lasting impact on how he thought drums should sound.

His drums sounded so great too, which was certainly a testament to his “touch” rather than the recording technology of the day. Now I realize that the way I heard those drums all those years ago, before I’d ever touched a drumstick, became my ideal of how drums ought to sound. (Traveling Music, p. 133)

To give you an idea of a few of the songs Blaine played on in the 1960s alone:

- "Can't Help Falling in Love" – Elvis Presley (12/18/61)

- "Be My Baby" - The Ronettes (1963)

- "Everybody Loves Somebody" – Dean Martin (07/11/64)

- "Help Me, Rhonda" – The Beach Boys (05/01/65)

- "Mr Tambourine Man" – The Byrds (06/05/65)

- "I Got You Babe" - Sonny & Cher (07/31/65)

- "These Boots Are Made for Walkin'" – Nancy Sinatra (02/05/66)

- "Monday Monday" – The Mamas & the Papas (04/16/66)

- "Strangers in the Night" – Frank Sinatra (07/02/66)

- "Good Vibrations" – The Beach Boys (10/29/66)

- "Mrs. Robinson" – Simon & Garfunkel (05/04/68)

- "Aquarius/Let the Sunshine In" – The 5th Dimension (04/12/69)

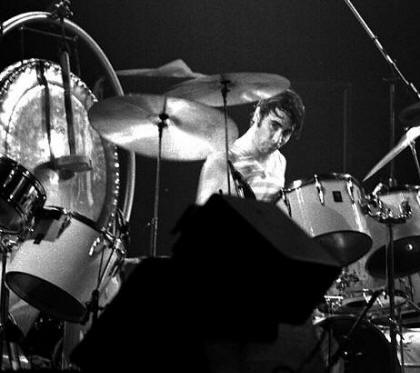

Keith Moon: The Who

Keith Moon's intuitive sense of phrasing influenced Peart and how the drums could frame the vocals. But Moon also opened up a new approach for rock drumming. In his first interview with Modern Drummer in 1980, Peart said, "Certainly Moon gave me a new idea of the freedom and that there was no need to be a fundamentalist. I really liked his approach to putting crash cymbals in the middle of a roll." (This approach shows up most famously in Peart's first solo fill (MP3) in "Tom Sawyer.")

Peart also saw the connections between Keith Moon and Gene Krupa:

I think (Gene Krupa's) rock 'n' roll heir was probably Keith Moon. In fact, I see a lot of direct similarities between their playing styles, even though Keith Moon showed even more abandon and was more sloppy. But he was a drummer who really captured my imagination because he was so free and so exciting because of his freedom. It opened me up. (Rhythm, March 1987)

To get an idea of the energy and creativity of Keith Moon — as a drummer and a performer — watch this in-studio video of "Who Are You."

Even though Moon was a significant influence on him, Peart would find out that he was wired much differently than his hero. In an August 1983 Modern Drummer "Ask a Pro" column, Peart explained Moon's influence:

It is certainly true that Keith Moon was one of the first drummers to get me really excited about rock drumming. His irreverent and maniacal personality, as expressed through his drumming, affected me greatly. To me, he was the kind of drummer who did great things by accident rather than design. But the energy, expressiveness and innovation that he represented at the time was very important and great. It is ironic that I wanted to be in a band that played Who songs and, when I finally got into one, I discovered that I didn’t like playing drums like Keith Moon. I liked to be more organized and thoughtful about what I did and where. I was fortunate enough to see The Who many times during the late '60s and early '70s and it was very sad to watch him decline and expire from the sheer exuberance of his life. There have been many other great drummers who have taught me things and inspired me, but "his like we shall not see again."

In an interview with Michael Portnoy for Rhythm (January 2007), Portnoy zeroed in on three of Peart's influences, including Buddy Rich, Michael Giles, and Keith Moon:

Mike Portnoy: The next drummer who I can hear a bit of an early influence is Keith Moon. Having done a Rush tribute and a Who tribute back to back, I was able to see the surprising similarities between the two of you. Although you are an incredibly disciplined and calculated drummer, and Keith was completely reckless and spontaneous, somehow I can still hear a lot of his influence in your early style, especially on Fly By Night.

Neil Peart: Yeah. It's his phrasing for me. It's a constant and continuing influence. I saw a TV documentary on the making of Who's Next, and Roger Daltrey was in the studio just bringing up the tracks and talking about how Keith Moon framed the vocals. It's so obvious from Tommy and Who's Next and his mature playing just how sensitive he was to the song. I absolutely still use phrasing ideas from Keith Moon because that was his magic. He seemed to play chaotically but it wasn't — it was an intuitive sense of musical phrasing.

Mitch Mitchell: Jimi Hendrix

One Saturday morning during my drum lesson at the Peninsula Conservatory of Music in St. Catharines, Ontario, I remember my teacher playing a record, then telling me, 'this changes everything.' It was Jimi Hendrix's Are You Experienced?, with Mitch Mitchell's artful and innovative drumming. (Zildjian.com, January 2003)

After watching Peart perform in St. Catharines, guitarist Joe Szilagy (who would later join Peart in the Majority) recalled the influence of Mitchell in his playing:

I did watch the tail end of (Peart's) set, and as they were packing up, I went up to Neil and told him I liked his drumming, and that he really reminded me of Mitch Mitchell, especially with regards to the type of drum rolls Mitchell did in "Purple Haze," etc. Neil smiled and thanked me, but said his main influence was Keith Moon, which surprised me, since I didn't notice any particular resemblance in style between them. (As told by Joe Szilagy, 2014)

Ginger Baker: Cream

His playing was revolutionary — extrovert, primal, and inventive. He set the bar for what rock drumming could be. I certainly emulated Ginger's approaches to rhythm — his hard, flat, percussive sound was very innovative. Everyone who came after built on that foundation. Every rock drummer since has been influenced in some way by Ginger — even if they don't know it. (Rolling Stone, August 20, 2009)

The excellent documentary Beware of Mister Baker explores Baker's mercurial personality and genius behind the drums. Here are two quotes in that documentary by Peart:

He was really at the forefront of a

complete revolution of rock. It's hard to find fault with the notion

that he was the pioneer of a rock drummer. There was no context,

there was no archetype. He is the archetype. (25:49 in Beware of Mr.

Baker)

Ginger Baker's most notable

achievement that should be recognized is the first rock drum solo.

And me as a 15-year-old kid, I was like, "Yeah, yeah! That's the

right drummer I want to be!" (1:02.30 in Beware of Mr. Baker)