4. Later rock influences: Late 1960s-1970s |

|

Updated: 07/04/2022

By the late 1960s and early 1970s, many drummers were starting to elevate the instrument to new levels. Peart wrote of this time and the drummers who influenced him:

Soon there were other adventurous and accomplished rock drummers, like John Bonham, Michael Giles (the first drummer with King Crimson and a very important influence on me), Bill Bruford with Yes, his replacement Alan White, Phil Collins with Genesis, and certainly Billy Cobham and Steve Gadd, who must have influenced every drummer in those days. (Zildjian.com, January 2003)

Carl Palmer - Emerson, Lake, and Palmer

Carol Palmer would be another drummers who influenced Peart: "I got into a more disciplined style later on as I gained a little more understanding on the technical side. People like Carl Palmer..." (Modern Drummer, April/May 1980)

In this 1973 video of Carl Palmer, there are several concepts that Peart would borrow in later years, including the array of percussion, integrated electronics, and a rotating riser.

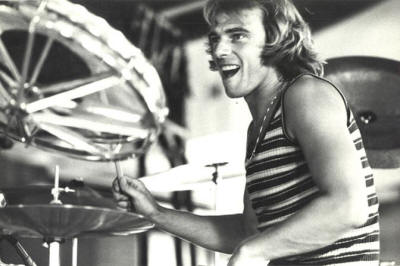

Phil Collins: Genesis and Brand-X

The body of ("YYZ") is influenced by the side of rock/jazz fusion which leans more towards rock, like Brand X, Bill Bruford, and some of Weather Report's work. (Modern Drummer, January 1983)

Peart also wrote the following about Phil Collins in a Rhythm magazine article entitled "I Love Phil" (August 20, 2011):

Phil

Collins was an enormous influence on my drumming in the '70s, and

thus remains a part of my playing even today. His recorded drum

parts with Genesis and Brand X in those years were technically

accomplished, yet so musical—even lyrical. His

rhythmic patterns were woven into the intricacy of the music, while

lending a smooth, fluid pulse to the songs and extended

instrumentals. His fills were imaginative and exciting, alive with

energy and variety, while the refined technique was

always in the service of the music. Even within those fills, Phil

applied a jazz drummer's sense of dynamics, which also guided

his ensemble playing, and inspired me to try to incorporate that

sensibility into my own triple-f approach.

Plus, his

drums sounded so good. Good-sounding drums are always the result of a

good-sounding drummer, and speak of the players touch. Phil's

combination of that quality and the natural drive of his playing

produced truly melodic-sounding drum parts—flowing and musical. One

outstanding piece of that reflected all of those qualities was the

Genesis album Selling England by The Pound, from '73. In the

summer of '74, just before I joined Rush, I attended one of the

shows on that tour (at the Century Theater, Buffalo, New York), and

it was simply a galvanising performance, by him and all of that

excellent band. The music from that night's show echoed in my head

long after, while Phils vocal performance "More Fool Me", was a

harbinger of a whole other career to come...

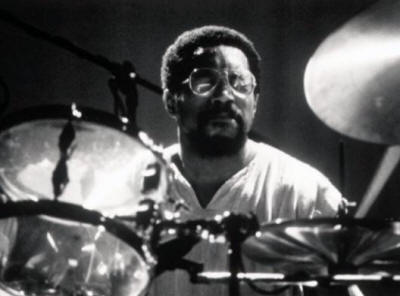

Billy Cobham - Mahavishnu Orchestra, Miles Davis, and more

In the press release for Burning for Buddy, Peart wrote about Billy Cobham:

Bill is a legendary modern jazz player, and has influenced a generation of drummers through his work with the Mahavishnu Orchestra, Miles Davis, Quincy Jones, Freddy Hubbard, George Benson, many releases on the CTI label in the '70s, his own group Dreams, and most recently, Peter Gabriel.

Peart also credits Cobham with the inspiration for riding to the "x-hat" on the upbeats in "Far Cry," as well as many other Rush songs:

In the bridge (of "Far Cry"), or pre-chorus, sections, I'm playing on the ride with the "x-hat" on the upbeats (the Billy Cobham revelation from the 70s, which he told me he first heard played by a guy in some bar), interspersed with rising double-bass-pedal triplets (thank you Tommy Aldridge) and China accents (that new "rattler") with the snare. (Modern Drummer, August 2007)

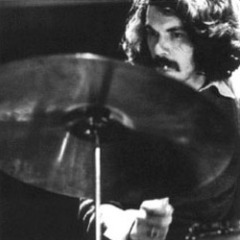

Michael Giles - King Crimson

Peart said of Michael Giles, who was the first drummer with King Crimson:

(He) was a very big influence on me stylistically and arrangement-wise—how to approach putting together a piece dynamically, how to use lots of fills but in a cool way—all of the stuff that I really wanted to do, he would use. He was an important influence. (Canadian Musician, 1994)

In an interview in Rhythm (January 2007), Mike Portnoy asked Peart about Michael Giles' influence on his playing:

Mike Portnoy: The third influence, and tell me if I'm right on this, is Michael Giles of King Crimson? Some of Michael's playing on In The Court Of The Crimson King, especially his snare work, could easily be mistaken for your early drumming.

Neil Peart: Oh, big time. Not only the early King Crimson but MacDonald and Giles too, it is everything I wanted. It was both disciplined and exciting. He was so fired up by what he was doing, but it was contained within a structure. His fill construction and sense of ensemble playing and orchestrating a part was unparalleled and very underrated.

Bill Bruford - Yes, King Crimson, UK

In one of his Bubba's Book Club reviews, Peart reviewed Bill Bruford's autobiography and wrote about Bruford's influence on his own playing:

Bill Bruford found early success with the English rock band Yes, early favorites of mine, and his playing on their first five albums was a strong influence on me in the early 1970s. As a struggling nineteen-year-old drummer recently moved to London, working behind the counter of a souvenir shop on Carnaby Street, I would pound the Sweda cash register in time with Bill’s drumming on Time and a Word and The Yes Album. And it wasn’t just the drumming that inspired me—in those days, with those bands and those musicians, it was about their entire approach to what they did: the philosophy, the purity, the sincerity, the integrity. The genre called “progressive rock” is much maligned today, of course (to quote a previous review on another topic, “for complicated political reasons that we needn’t get into right now, thank you”), but at its best progressive rock stood for an honesty that is rarely present in popular music today.

Alan White - Yes

Aside from the quote at the top of the page about Alan White being Bill Bruford's replacement in Yes, I haven't found any other specific quotes about White's influence on Neil Peart's playing. However, as a fan of White's drumming with Yes and other bands, I'd like to offer my own perspective (especially for those who might not be familiar with him). These views are my own and not associated with Neil Peart.

When Bill Bruford left Yes in July 1972, White took over the drum throne. Before Yes, White was an in-demand drummer, playing with ex-Beatles John Lennon (on Imagine and the "Instant Karma" single) and George Harrison (on All Things Must Pass). He also had experience playing with Ginger Baker's Air Force and Joe Cocker.

While Bruford's more subtle, jazz/fusion approach helped to define and launch Yes onto the world stage, it would be White's more rock-oriented style and R&B feel that drove the band's sound forward through the next four decades. White had the stamina and technique to play comfortably on side-long progressive epics ("The Gates of Delirium") and shorter less complex songs ("Going for the One" and "Don't Kill the Whale").

I joined the Yes bandwagon during the 1980s as "Owner of the Lonely Heart" and other songs from their multi-Platinum 90125 dominated radio. Yes's stop on that tour in Pullman, Washington, in spring of 1984, was my first arena rock concert. (Rush's Grace Under Pressure in Tacoma, 1984, was my second.) That Yes concert introduced me to many songs in Yes's back catalog, and soon I began to discover their rich history. The live album Yesshows (released in 1980) with its first three songs, "Parallels," "Time and a Word," and "Going for the One" echoed Rush on several levels. Much of this had to do with the rhythm section of White and Chris Squire on bass (also one of Geddy Lee's influences), but there was also Jon Anderson's higher- register vocals and the band's willingness to experiment. In particular, White's drum part on "Going for the One" shared many of the same qualities of a Peart drum part: a strong backbeat, creative and explosive fills (when needed), playing over the bar line, and emphasizing the vocal line.

White continued his solid, inventive playing with Yes (as well as on the mind-blowing Torn, Levin, and White side project). Fortunately, since we both lived in Seattle, I had the pleasure of meeting Alan a few times and found him to be a generous and down-to-earth person. In 2011 had the opportunity to do an extensive interview with him about Yes and Torn, Levin, and White.) In 2022, after a short illness, Allan White passed away.

Steve Gadd

As with Alan White above, there are no specific quotes from Peart about Steve Gadd's influence on his early playing (although there are more quotes about Gadd's influence after they worked together on Burning for Buddy). To repeat Peart's quote, Gadd "must have influenced every drummer in those days."

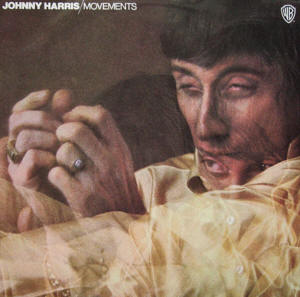

Harold Fisher - Johnny Harris' album Movements

In an article for Zildjian.com, Peart used it as an opportunity to call out a drummer who influenced him on the Johnny Harris album Movements. But for many years, Peart didn't even know the drummer's name:

London is always a crossroads for young bohemians, and I

worked with a number of expatriates from all over the

world. During the day we took turns choosing the music

to play in the shops, and one Persian guy, Ahmed, always

liked to hear this instrumental record called

Movements, by an

arranger/conductor named Johnny Harris. After many

listenings, I gradually began to appreciate the subtlety

and sophistication of the drumming, and the jazz-based

technique which combined funk overtones and rock power

and dynamics.

More than anything, I loved the construction of the drum parts,

so intricately designed and elegant, in styles ranging from laid-back

funk to driving energy, and delivered with a great natural sound, and

perfect time and feel. Twenty years later I listened again to that

record and realized how much the drummer had influenced me, especially

in the building of drum parts for songs-and I didn't even know his name!

There were no musician credits on the album, and it was

only after a remarkable trail of internet searches by a friend of

mine, Brian French, that we learned who my anonymous tutor had been. I had guessed that it might be Kenny Clare, a well-known British

drummer in those days who played a similarly exciting and musical

style with such people as Tom Jones and Tony Bennett (with whom I

had seen him play at the London Palladium in '70 or '71 with Brian's

brother, Brad, my flatmate in London, or even perhaps Michael Giles

again, but it turned out to be someone I'd never even heard of: a

British session drummer named Harold Fisher. So after all these

years, I'd just like to say, "Hats off to Harold." (Zildjian.com,

January 2003)